Jacinta Orillo | Medical Laboratory Technician

A QUIET DOOR

Death is only a quiet door,

In an old wall.

(Nancy Byrd Turner)

My introduction to the hospital mortuary was just that—a quiet door, in an old wall. An unassuming, white wooden door, set into a grey brick wall, tucked away in a basement that smelt like dampness and dust, unaltered since its construction in the 1950s.

Death is a door in an old wall. A white wooden door; steel fridge door. In my experience there are no signs to say where the mortuary is. Both those I’ve worked in were unmarked—you wouldn’t know they were there.

Death is the sound of a fridge compressor sparking up, forever cooling. The fans are loud and drown out all thoughts. They cause stray hairs to blow across half closed eyes, body bags to ripple making you look twice—was that movement? Of course it wasn’t.

Death is peace and grace. It is freshly manicured nails clutching flowers, a faint whiff of talcum powder, faces no longer taut with stress and pain. It is clean pyjamas, serenely closed eyes, hands folded gently over stomachs, photos of loves ones tucked underneath.

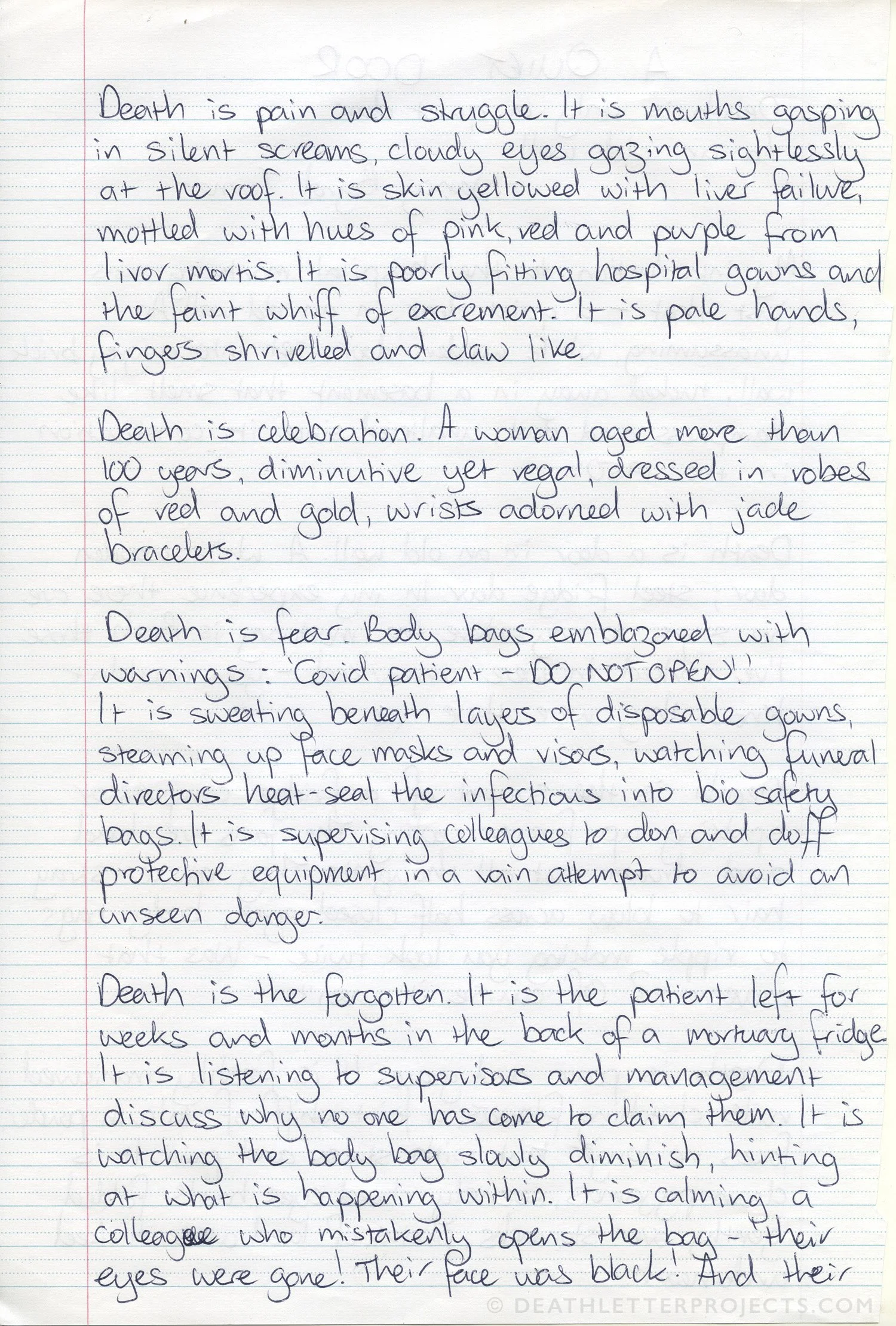

Death is pain and struggle. It is mouths gasping in silent screams, cloudy eyes gazing sightlessly at the roof. It is skin yellowed with liver failure, mottled with hues of pink, red and purple from livor mortis. It is poorly fitting hospital gowns and the faint whiff of excrement. It is pale hands, fingers shrivelled and claw like.

Death is a celebration. A woman aged more than 100, diminutive and regal, dressed in robes of red and gold, wrists adorned with jade bracelets.

Death is fear. Body bags emblazoned with warnings: Covid patient—DO NOT OPEN. It is sweating beneath layers of disposable gowns, steaming up face masks and visors, watching funeral directors heat-seal the infectious into bio safety bags. It is supervising colleagues to don and doff protective equipment in a vain attempt to avoid an unseen danger.

Death is the forgotten. It is the patient left for weeks and months in the back of a mortuary fridge. It is listening to supervisors and management discuss why no one has come to claim them.

It is watching the body bag slowly diminish, hinting at what is happening within. It is calming a colleague who mistakenly opens the bag—‘their eyes were gone! Their face was black! And their teeth…they had no lips, just their teeth.’

It is all this and more.

It is unknown careless mistakes made by nursing staff only for them to be discovered by people like me.

It is helping a funeral director roll over a patient who had accidentally been left face down for days. It is suppressing a gasp as the face lands inches from my own. Skin as purple as plums, nose and lips swollen yet flattened as if pressed against glass. Blood and fluids leaking from every orifice, causing the skin to blister. Hands twisted and contorted in ways not natural, due to the weight of the body pressing down for so long. It is privately crying in the corner once it is complete….

It is assisting a manager to help wash the blood from a woman left to bleed slowly out for days from uncovered IV lines. It is wiping away with reverence the mess it has made to her beautiful floral dress, and shuddering at how cold her skin feels. It is feeling how cold her skin was even to this day.

Death is a quiet door, a white van, a steel stretcher, a blue body-bag.

Death is inevitable.

—Jacinta Orillo (2024)

Editor’s note: Jacinta began working in a hospital mortuary just prior to the coronavirus outbreak. She worked at the mortuary for two years. She’s now working as a medical laboratory technician and plays roller derby and writes in her spare time.

The Death Letter Project welcomes your comments and feedback. Please feel free to leave a comment on our Facebook page or alternatively submit a message below.